About this project

“What is the snowball portfolio?”, I hear you cry.

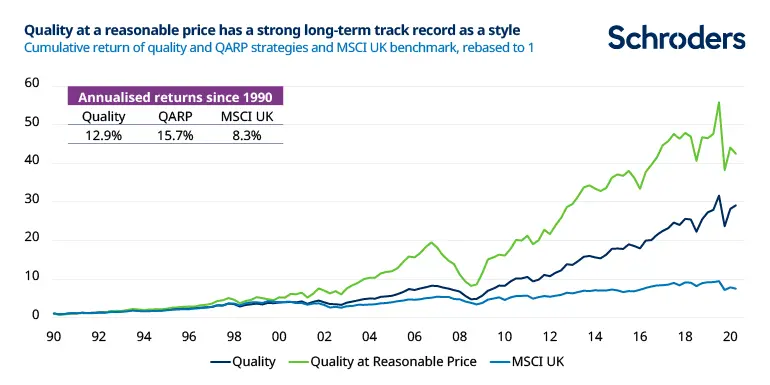

The Snowball Portfolio is a value-based asset portfolio comprised of quality compounders.

And if that incredibly dull sounding sentence hasn’t already caused you to switch your focus onto something more interesting, you’re in good company on this website. In essence, I look for value-investment opportunities (wherever they exist), and use them as a vehicle for compounding the portfolio size over many years.

However, pumping money into random assets is not enough. I want to buy quality businesses at a reasonable price.

That is the essence of the strategy. I look for three main characteristics in businesses before adding them to the portfolio:

• Large moats, so can charge more than their competitors.

• Reinvest that money efficiently, increasing FCF year-on-year.

• Aren’t overpriced.

Much like a snowball rolling down a hill, time and consistency are the two biggest assets in building substantial wealth. What starts off small can quickly grow, compounding in size.

The Investment Crystal Ball

"Rule No 1: never lose money. Rule No 2: never forget rule No 1."

The premise of successful investing is that an investor does not pay more for an asset than it is worth.

If you agree with this statement, then it stands to reason that you also agree that an investor should (at least try to) determine the value of the asset they intend to purchase, beforehand.

There are those buy assets with only the hope that somebody will be willing to buy it for more at a later date. Those who buy a stock simply because “it is going up”.

I would argue that these people are not investors, and instead are speculators or gamblers. In fact, there is even an aptly named term for this behaviour - The Greater Fool Theory.

Valuing an asset is the only true way of determining whether you are buying at a fair price. Of course, buying assets at a fair price is not a prerequisite of investing, but it does give you a huge advantage in the long run.

Furthermore, not all estimations of value will be correct. In fact, most (if not all) will be wrong. There is no way to accurately predict what the economic conditions or company financials will be like tomorrow, let alone in 3, 5 or 10 years time.

Accounting for Risk

So why bother trying to value an asset if we know the result will be wrong?

"Success in investing comes from not being right, but from being wrong less than everyone else"

We know our value estimations won’t be precisely 100% correct. But they will be “close” to a fair value if we do our analysis properly. Maybe we estimate the fair value for a stock is $45, while the true “fair value” is $40. We’re pretty close.

Unfortunately, buying an asset for $45 if it’s really worth $40 isn’t a good business decision.

That’s where we use the investor’s favourite tool in the value-investing toolbox - the margin of safety.

The margin of safety is a financial safety net. Even though we’ve estimated a fair-price of $45 for this asset, we factor in that we might be wrong. In fact, we know we are!

We account for a margin of error in our judgement (20% for example). So even though we think the asset is worth $45, we only buy it if the price is 20% less than that ($36).

"Value means exactly that, figuring out what a business is worth and only buying it when it’s worth a lot less."

The Investing Toolbox

The next question to answer then, becomes: “How do we find value?”.

We need to be able to determine an estimate of intrinsic value for an asset before we consider adding it to the portfolio. Making estimations of value involves a lot of guesswork, so it's helpful to know a lot about the industry in which the business operates.

As mentioned above, the elusive “intrinsic value” is impossible to estimate with 100% precision, but we do have quite a few tools in the investing toolbox that will help.

Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) models and Reverse Discounted Cash Flow models (Reverse DCF) tend to be the most popular methods for this. However, I prefer a different approach.

Price Implied Expectations (PIE) is a similar yet distinct method. It reduces much of the guesswork by using the current stock price to estimate the market's consensus. The calculations are much simpler, there are fewer guesses, and the result gives a clearer picture of whether the asset is under or over valued.

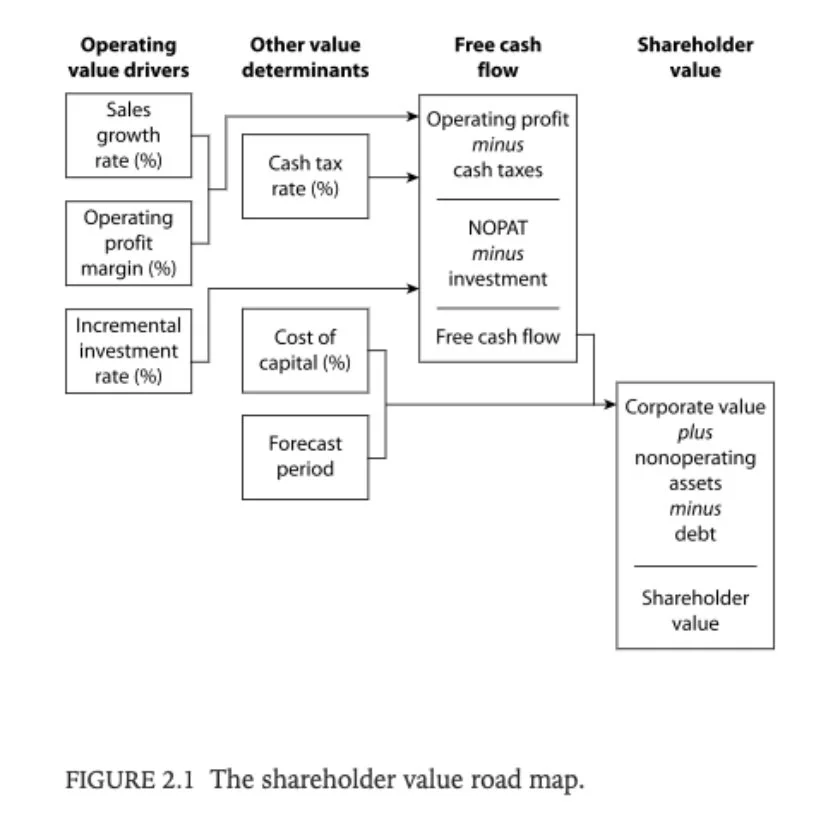

In the flow-diagram below taken from Expectations Investing by Michael Mauboussin, the valuation process is boiled down to just 6 variables.

Other factors will also have an effect. Such as Insider Ownership, Risk Free Rates, etc… However, this is the overall framework I use for assessing the potential for each investment made.

Investing is very simple once you understand how companies create value, and whether the price of the asset is an accurate reflection of that future value.

Quality & Compounding

Buying assets for less than their intrinsic value is an excellent way of compounding wealth. Eventually, the market will realise its mistake and correct the price upwards. (Or downwards if the stock is over-valued).

However, there is a theory that it is actually impossible to “beat the market”.

The theory states that the price of an asset (at any point) accurately represents all available information about that asset at that given point in time. Therefore, stocks trade at the fairest value, meaning that they can't be purchased undervalued or sold overvalued. This theory is called the Efficient-Market Hypothesis.

The market is full of professional investors who have access to more data than we do. Big corporations that spend millions of dollars to get access to real-time data as soon as humanly possible. How can we hope to compete against them?

Well, if you’re on this website, and have reached this far down the page without getting bored, you must (at least somewhat) agree with me that that the Efficient Market Hypothesis is incorrect.

For example, think of a publicly traded company - any will do.

Once you have a company in mind, go look up the stock price over the last 52 weeks.

Most likely, the stock price will have moved between quite a large range in this time.

I’ll use Microsoft as an example, since it is the largest company in the world at the time of writing. And no doubt has thousands of incredibly smart financial analysts following this company on a daily basis.

The market cap of Microsoft within the last 52 weeks has bounced between $2.3T and $3.3T. (Low: $309.45. High: $450.94).

So, if we were to believe in the Efficient Market Hypothesis, and the market is entirely efficient, how can it be that the value of Microsoft has changed by one trillion dollars in such a short space of time?

Can the largest company in the world really be worth $2.3T one day, and then $3.3T a few months later? Surely, Microsoft’s underlying business model can’t have changed that much within 12 months to justify such a large change!

Therefore, the question at the heart of value investing becomes: why do share prices move around so much, when the underlying economics of the company do not?

Mr. Market

The father of Value Investing, Benjamin Graham, tried to answer this question with an analogy.

Imagine that tomorrow morning, the stock market no longer existed, and in its place was a crazy man named “Mr. Market”. Unfortunately, Mr. Market is prone to wild mood swings.

Each day, Mr. Market would offer to buy and sell shares at random prices. The decision would be entirely up to you, but each day you had three choices:

1 - You could buy the shares from Mr. Market at his proposed price. 2 - You could sell your shares to Mr. Market at his proposed price. 3 - You could do nothing.

Sometimes, Mr. Market is overjoyed and will propose very large prices. On these days, it makes sense to sell your stocks, taking advantage of his generosity.

On other days, Mr. Market will be extremely sad, and offer quite low prices. Maybe he’s not been sleeping well recently. On these days, it makes sense to buy stocks from him at these deflated prices.

Mr. Market is a very simple analogy, probably designed to appeal more to children than grown investors, but the analogy is accurate.

Value Investing

So, we know that the price of an asset will fluctuate wildly, while the underlying economics of the asset remain very much the same.

We also know that it is possible to accurately estimate the true intrinsic value of an asset using the financial data available to us. Unfortunately, we know our estimations will be wrong, so we should make use of our financial safety net and factor in our margin of safety.

Using our valuations, we wait patiently for Mr. Market to have a bad day, and offer us a price below this value. This leaves a lot of upside potential, with relatively little downside. This process is known as Value Investing.

Doing this consistently over many years allows the effects of value investing to compound. What starts off small quickly increases in size.

"Compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world. He who understands it, earns it. He who doesn't, pays it."

It’s this ‘Eighth Wonder of the World’ that has allowed Warren Buffet to use the teachings of Benjamin Graham to compound his wealth from $100,500 to $885,000,000,000 in just 68 years. (An annual return of 26.5% per year).

This method is exactly what I intend to emulate with the Snowball Portfolio.

And no, my ego isn’t so big to delude myself into thinking I can beat Warren Buffett - the greatest investor of all time. But I do think I can beat the S&P 500. Mainly because so few people try, and I do believe that the individual investor has a huge advantage by managing their own money.

You can see how I'm doing in the Portfolio section of this website.

All the assets in the portfolio will have a detailed write-up, justifying its presence and weighting.